APOLLO RETROSPECTIVE

July 20, 1969

For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing,

the Space Policy and Research Center at the University of Washington

presents these reflections of the Apollo Program by faculty, alumni and colleagues

who were inspired to work toward a future in air and space.

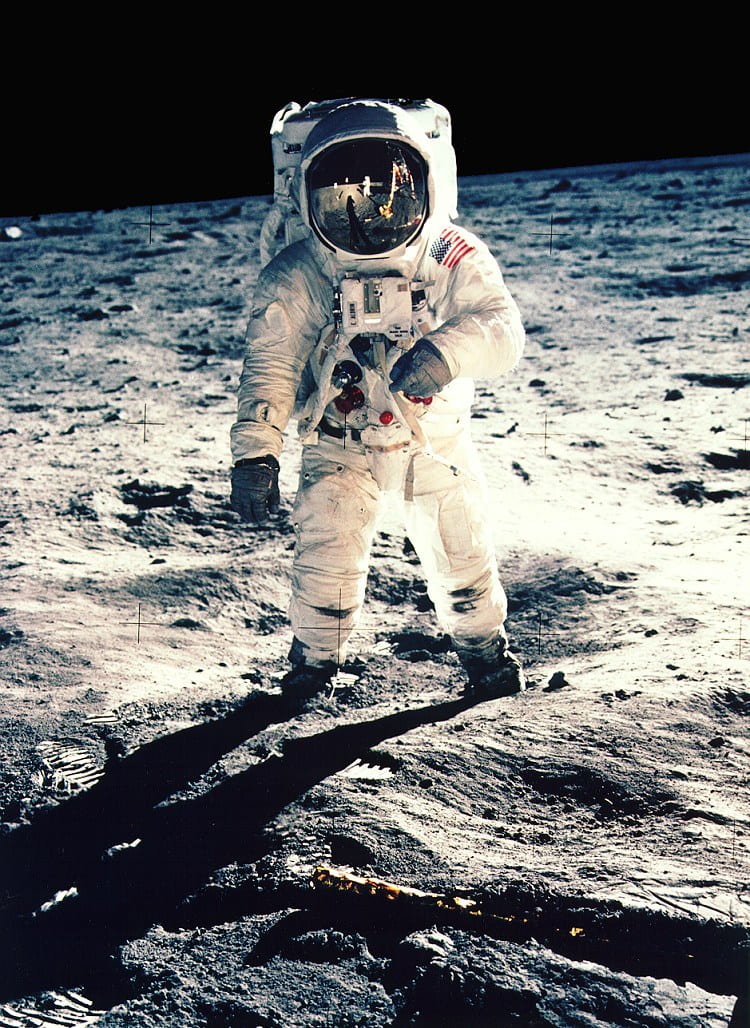

The Apollo Program was the largest non-military effort in history, engaging over 400,000 people from NASA and over 20,000 companies in the effort. The collective attention toward television sets to watch the real-time developments was unprecedented, especially with the success of Apollo 11, with Americans and others around the world watching Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin take the first steps on the moon with awe and relief.

These historic developments influenced politics, national pride, advances and investment in STEM, and more. Apollo captured imaginations, inspired children, ignited careers, and motivated a nation.

Enjoy the UW voices and photos collected here from faculty, alumni, and colleagues whose paths were steered by Apollo. From surprising, once-secret connections to the Saturn V development to lifelong passions for air and space travel, we offer this retrospective on the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11.

To the moon . . . 50 years ago.

I often ask my students what prompted their interest in aerospace. Did they have an “aerospace moment?” Was it seeing a Space Shuttle launch, their first airplane trip, the roar of a fighter jet at an airshow, pictures from Mars?

I urge them to always remember and lean on that excitement to help get through all the courses, exams, projects, reports, and deadlines that come with a demanding engineering program such as ours.

My “aerospace moment” is as alive today as it was in junior high school. It was December, 1968, and I was watching coverage of Apollo 8 on my grandparents’ black and white TV.

Read more from Jim Hermanson . . .

I had been following the space program somewhat, but that was when it truly “hit me” that we were actually going to the moon! At that moment I knew what I wanted to do for a career.

My parents graciously endured my youthful, over-the-top enthusiasm for space travel. This included sitting in a separate room with a “TV dinner” watching every minute of the coverage of Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969, and staying awake for nearly 48 hours in front of the TV during the lunar stay of Apollo 15.

All that, plus being a Seattle native, made pursuing a degree in aeronautics and astronautics at the University of Washington the obvious path. I have held onto space travel as the central theme in my career, first at Boeing on the Inertial Upper Stage program, then combustion research in graduate school, followed by high-speed propulsion work at United Technologies Research Center. Ultimately this led to teaching aerospace engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute and now at the UW.

Naturally, I also applied to the NASA astronaut program for a number of years. Well, NASA didn’t choose me, but what I did was even better: sharing my passion for space with our students. I have told them that I am counting on them to get us to Mars, but wherever their careers may take them, to always remember their own “aerospace moments.”

“Second star to the right and straight on till morning!”

– Peter Pan (and James T. Kirk)

Jim Hermanson

Professor, UW Aeronautics & Astronautics

UW BS A&A 1977

“My parents graciously endured my youthful, over-the-top enthusiasm for space travel. This included sitting in a separate room with a ‘TV dinner’ watching every minute of the coverage of Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969, and staying awake for nearly 48 continuous hours in front of the TV during the lunar stay of Apollo 15.”

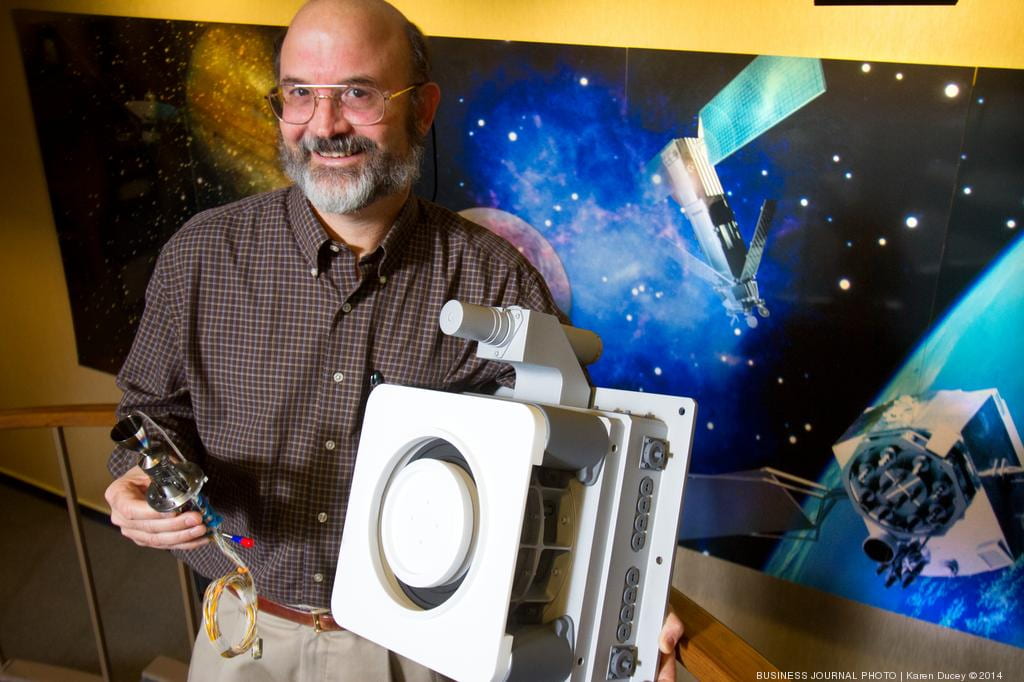

Above left: Jim Hermanson in the Apollo era, already a space travel superfan. And above: Hermanson today with the same models of the Saturn V and the Apollo Spacecraft.

I was four years old the year humans first landed on the Moon. Even before the landings, I was very interested in space. I watched Star Trek every afternoon, and I had a NASA-themed tin lunchbox with pictures of the rockets, spacecraft, rovers, and astronauts involved in space exploration.

Read more from Stanley Love . . .

I don’t recall seeing the televised Apollo 11 moon walk (probably past my bedtime) but I do remember watching one of the Apollo splashdowns (I think it was Apollo 16) in my elementary school. They wheeled a black-and-white TV set into the classroom on a tall cart, and we all watched the little capsule parachute down to a safe landing in the water.

Incidentally, the commander of Apollo 16 was John Young. About a quarter of a century later I found myself in Houston, Texas, wearing a brand new suit, interviewing to become a new astronaut . . . and sitting across the table from me was the chief of the astronaut selection board, John Young. It took three separate interviews across three years to convince the guy I’d watched come home from the Moon when I was in grade school that I’d be a good hiring prospect . . .

Stanley Love

Astronaut, NASA

UW MS Astronomy 1989 & Ph.D. Astronomy 1993

“They wheeled a black-and-white TV set into the classroom on a tall cart, and we all watched the little capsule parachute down to a safe landing in the water.”

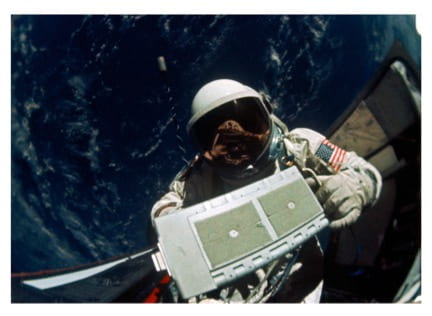

Stanley Love, at left in center, on the P&O ocean liner “Oriana” en route to New Zealand in the Apollo era. Above, Love on a spacewalk during STS-122 in 2008.

I was in the control room during the Apollo 11 spacewalk as part of the “Lunar Stay” team. The Apollo 11 mission had different flight control teams for the Moon landing: The Descent Team for landing on the Moon, the Lunar Stay Team for the duration on the Moon, and the Ascent Team for lifting off from the Moon.

When one team was in Mission Control, the flight director would lock the door so no one would disturb that team of flight controllers. Otherwise it would have been chaos with hundreds of people in there distracting those on duty.

The rest of us in the teams that were not in Mission Control would wait in the staff support rooms around Mission Control. We were there listening and waiting. I knew Neil was not going to take a rest after landing before deciding to step out onto the lunar surface, so we were waiting for him to make that decision, and as soon as we heard the decision, my Lunar Stay Team moved into Mission Control, and the Descent Team moved out.

It really struck me that when they open the door and I’m walking in ready to sit at the console, I was going to be part of this amazing thing of with these guys walking on the lunar surface. My responsibility was making sure the extravehicular mobility units (EMU’s), the spacesuits and life support backpacks, were working and keeping these guys alive.

Read more from Jim Joki . . .

Everyone else is watching the damn TV and I’m there watching the monitors reading oxygen and temperature levels!

There were many mountains and valleys of highs and lows. Each team had a success, but then the stress level was still high because our astronauts were not home safe yet. Each team would leave in the dark and look up at the Moon, and it was amazing. But the next team had to go in and do its part. It was very emotional for all of us.

Apollo’s biggest legacy is what Neil referred to: It wasn’t just the astronauts – it was 400,000 people working on it from the janitors keeping the environment clean to the technicians. Everyone did a small part, and the joint effort was incredible.

Jim Joki

Apollo 11 Flight Controller, Lunar Stay Team, NASA

Obstetrician, UW Medicine

UW BS A&A 1965

“I knew Neil was not going to take a rest after landing before deciding to step out onto the lunar surface, so we’re waiting for him to make that decision, and as soon as we hear the decision, my Lunar Stay Team moved into Mission Control, and the Descent Team moved out.”

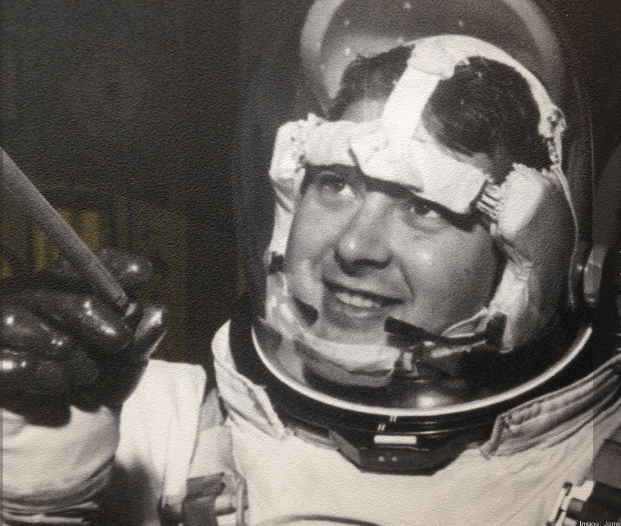

Above left: Jim Joki in a test spacesuit he engineered for the Apollo 11 mission. Above: After working on biological life support systems for astronauts in the Apollo Program, Joki shifted gears to obstetrics.

I was fascinated at a young age with airplanes and rockets. When Sputnik was launched in 1957, my family went to an observatory in the Northeast on a day trip and listened to the “beep, beep, beep” signal being transmitted from the first artificial satellite launched by the Soviet Union. It was exciting but a bit scary at the same time because the U.S. and the Soviet Union were engaged in the Cold War with threats of missiles being launched carrying nuclear weapons. I can remember praying every night that a missile wouldn’t hit my home and my family. Now the Soviet Union was first in space and poised to take control over future exploration.

Fast forward 12 years to when I was 20 years old, soon to be entering my junior year at M.I.T. studying aerospace engineering. I was already hooked on aeronautics and the space program. I had seen the Soviet Union dominate many aspects of the space race, including several firsts, but now the Americans were about to be first to walk on the Moon, the ultimate prize to win the space race. It was a surreal moment. My older sister and I sat up late at night, watching the Moon coverage, eerie black and white fuzzy transmissions lighting up our living room with no other lights on. I didn’t realize then that the world was watching too, united in a sense of higher purpose. One of us earthlings was now walking on another heavenly body. It is hard to comprehend the meaning even today.

Read more from Linda Dawson . . .

But 50 years later, I still yearn for increased human exploration and travel further than the Moon, more in line with sci-fi expeditions. I hope to see such travels in my lifetime.

I continued to live out my dream by working on the Space Shuttle Program as an Aeronautics Flight Controller at NASA Houston Mission Control. It was an exciting job, working with astronauts and other engineers developing mission objectives and flight rules. My career continued at Boeing and then into academia, teaching at the UW for over 20 years. My roots always remained in space (if that’s possible). I started writing at the end of my career and into retirement, publishing 2 books on outer space: The Politics and Perils of Space Exploration and Space Wars, both Springer publications. I remain and always will be a “space cadet.”

Linda Dawson

Senior Lecturer Emeritus, UW Tacoma

Former Mission Control Flight Controller, NASA

“My older sister and I sat up late at night, watching the Moon coverage, eerie black and white fuzzy transmissions lighting up our living room with no other lights on. I didn’t realize then that the world was watching too, united in a sense of higher purpose. One of us earthlings was now walking on another heavenly body.”

Left: Linda Dawson as a NASA Mission Control Flight Controller. Above: Dawson today as an author and Senior Lecturer Emeritus at UW-Tacoma.

Robert Breidenthal

Professor, UW Aeronautics & Astronautics

“The Apollo program was in many respects the high-water mark for America to date. In spite of all the ugliness and turmoil of the time, a giant team of 400,000 Americans pulled together to achieve something difficult and beautiful.”

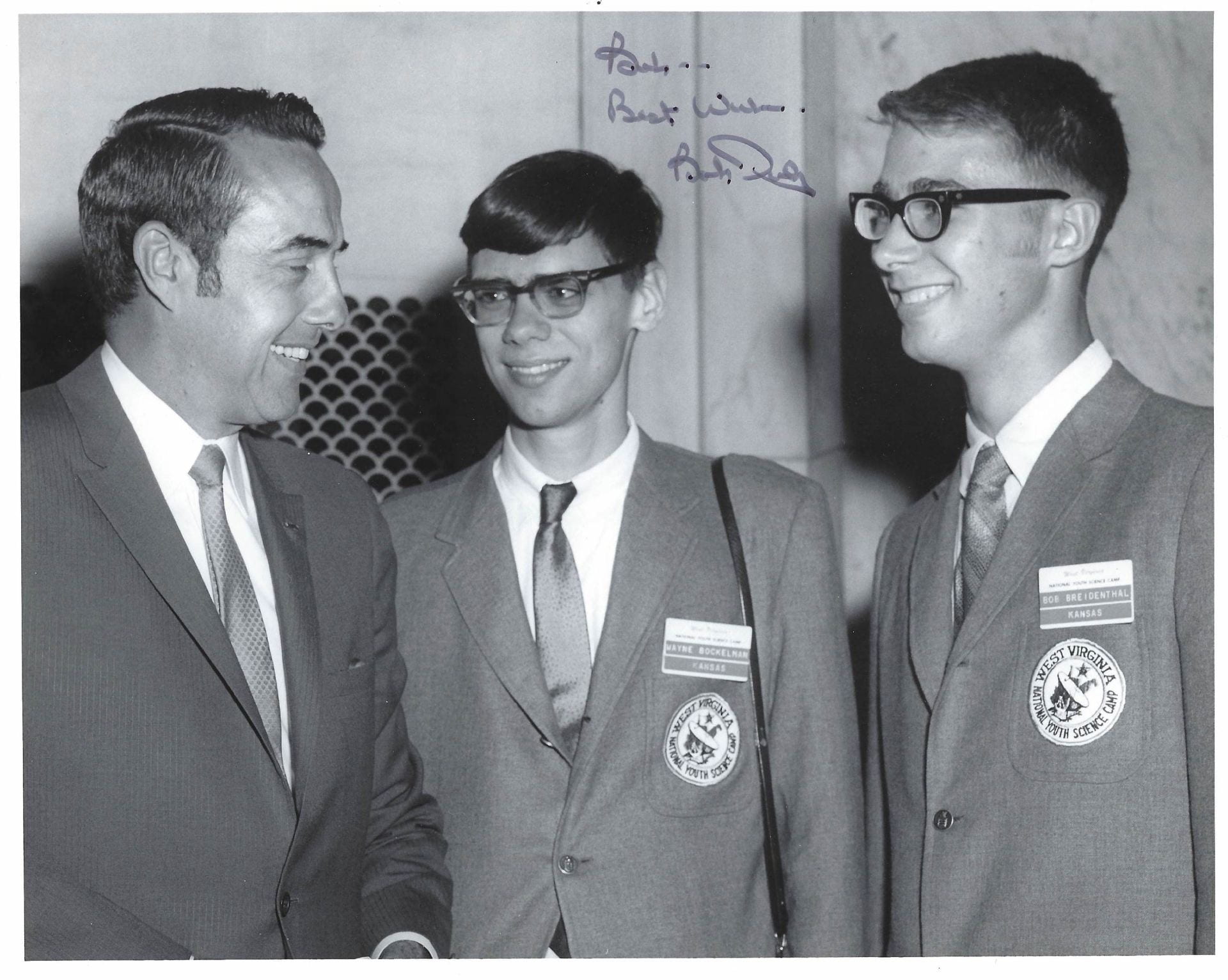

Above right: Bob Breidenthal (right) with Kansas Senator Bob Dole (left) and after representing Kansas with Wayne Bockelman at the National Youth Science Camp in the summer of 1969. Above: Breidenthal today.

I am old enough to remember even the Mercury flights. A manned launch was a high-risk proposition in those days. Kids got to stay up late or get up early to watch. Surrounded by the Vietnam War and domestic turbulence, the space program was a contrasting island of science and adventure. After seeing our beautiful blue marble floating in the inky blackness of space, just about every returning astronaut became an environmentalist.

In those days, test pilots lived dangerous lives. If I recall correctly, one third of John Glenn’s classmates died during their two-year Navy test pilot school. He went to lots of funerals.

Read more from Bob Breidenthal . . .

Not long before the launch of Apollo 11, my dad wrote to Buzz Aldrin, inquiring if his father was the Aldrin who had served on Guadalcanal during WWII.

An opinionated teenager, I immediately criticized my dad for troubling an astronaut at what must be a busy time. To my surprise and my dad’s delight, Aldrin promptly replied, confirming that his father had indeed been on Guadalcanal and passing along his regards.

Of course, the moon lander’s computer failed, and engineers at Mission Control had to make many quick life-or-death decisions. When the landing zone turned out to be full of lethal boulders, only the calm competence of Neil Armstrong averted an abort or worse. He came within a few seconds of running out of propellant. It was close. Never accepting individual credit, Neil always spoke about the team. There is only one NASA manned mission patch with no astronaut names on it: Apollo 11.

The Apollo program was in many respects the high-water mark for America to date. In spite of all the ugliness and turmoil of the time, a giant team of 400,000 Americans pulled together to achieve something difficult and beautiful. Along with many others, it inspired me to become an aeronautical engineer.

I was 11 yrs old when Apollo 11 landed on the Moon. I remember watching the landing at school on a black and white TV. We were all ready to become astronauts and we able to legally experiment with firecrackers and rockets in the backyard in those days. The landing itself is etched in my mind even after so many years because it demonstrated that extraordinary things could be achieved if people had big visions and worked together.

Those dreams were already present on TV through series like “Star Trek” and “Lost in Space” and in the news as the Cold War grew hotter. But with the landing it demonstrated that the dreams of science fiction could be made a reality.

But it was clear even then that the landing was just the beginning, and there was more hard work to follow if we wanted a sustained effort in space. I myself have tried to stay true to those dreams but the road has never been straight.

Read more from Robert Winglee . . .

President Kennedy’s words “we go to the Moon . . . and do the other things, not because they are easy but because they are hard” is still as relevant today as it was in the Apollo era. Similarly the innovations being developed for space flight have unforeseen major benefits for society then as they do today. I involve my students in these types of research projects and provide outreach to students across the country so that will be inspired to actively contribute to future developments on the ground and into space.

Robert Winglee

Professor, UW Earth and Space Sciences

Director, Washington NASA Space Grant Consortium

Director, NASA’s NW Earth & Space Sciences Pipeline

“But it was clear even then that the landing was just the beginning, and there was more hard work to follow if we wanted a sustained effort in space.”

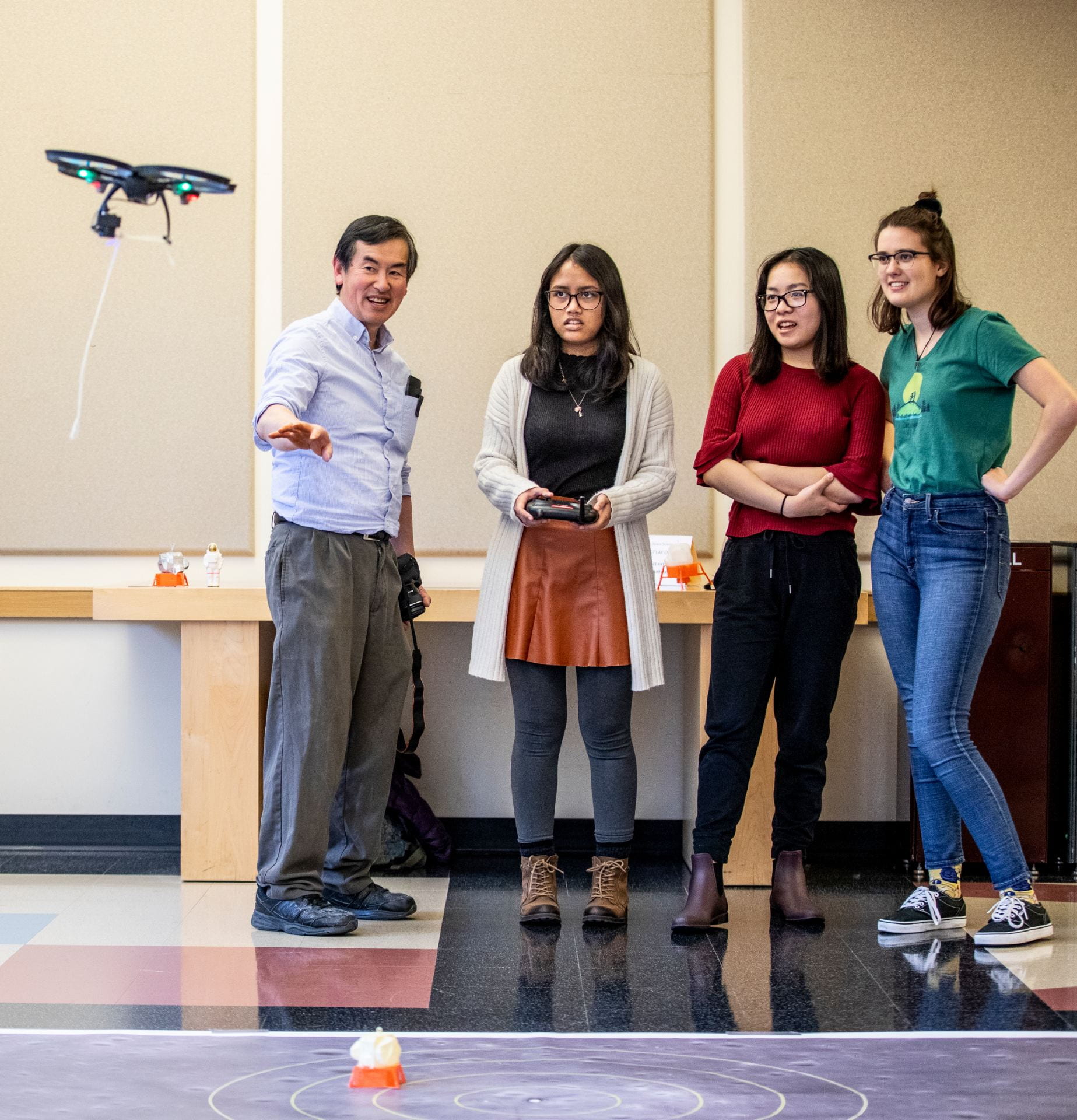

Above left: Robert Winglee in the Apollo era playing with fireworks in his backyard in Sydney Australia, with his brothers and neighborhood friend. Above: Winglee teaching in his UW lab.

George Jeffs, as president of Rockwell Aerospace, showed Queen Elizabeth II a display of an Apollo space capsule during her visit to California in 1983. Photo credit: Larry Armstrong / Los Angeles Times, Feb. 28, 1983.

Remembering George Jeffs (1925-2019)

“[Apollo] was a thrill in the precision of everything working in the way it was supposed to work. It was workhorse off the pad. It did everything it had to do during the boost phase. It was a ballerina in space. A ballerina! A ballerina and a wonderful work station and a hypersonic flying marvel on re-entry.”

– Jeffs in an interview with the College of Engineering in 2011

The UW lost one of its most extraordinary alumni in May 2019. Jeffs is widely recognized as one of the chief architects of the accomplishments of the United States in space. He directed Rockwell’s Space Division’s Apollo command and service module (CSM) program through nine lunar missions, as well as playing key roles in subsystems including the hatch, environmental controls, communications, and propulsion systems.

Jeffs was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom as part of the Apollo 13 Mission Operations team in 1970. His leadership in developing real-time management responsiveness led to the resolution of critical flight problems during the mission that converted “a potential tragedy into one of the most dramatic rescues of all time.” At the UW, he was named the 1980 A&A Distinguished Alumnus, was awarded the UW’s highest alumni honor of Alumnus Summa Laudate Dignate in 1985, and received a College of Engineering Diamond Award in 2011 for distinguished achievement in industry.

Heather Ross

Aeronautics & Astronautics Distinguished Alumna 2017

787 Project Test Pilot, Boeing

UW BS A&A 1985

“It took a generation, but I think that we are now seeing some of the creative inspiration that was sown as a result of the Apollo Space Program. Visionaries like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson, who have managed to surmount the huge financial barrier to entry to start their own space companies, grew up in a post-Apollo world.”

Heather Ross, above right in the red shoes with her family, in the Apollo era. Above: Ross test-flying a Boeing 787.

I was pretty young when Apollo 11 and its crew launched on their journey to the Moon. I remember my family were all assembled and watching the television, and I faintly remember puffy looking figures climbing down a ladder and bouncing on a gray landscape. I knew it was an important event because even though we really hadn’t followed much of the space program to that point, we were tuned in to see the Moon landing, like most everyone else.

When I think of how the Moon landing affected me, I can’t say that I consciously was aware of the event shaping me or the career path I chose. I was always more drawn toward vehicles operating in our atmosphere rather than beyond it.

Read more from Heather Ross . . .

I looked at the space program and pursuing a career in the space industry from a pragmatic rather than ideological perspective. The space program was owned by NASA, and NASA was a government organization that achieved great things when there was a strong advocate like John F. Kennedy in the White House, who would promote (and fund) space exploration and a lunar landing goal.

By the time I was in college, the emphasis in space pursuits had swung towards a more mundane space exploration goal and making orbital flights a routine event. It was a difficult goal to achieve, and necessary groundwork to lay, but it certainly didn’t excite the imagination quite like Apollo.

It took a generation, but I think that we are now seeing some of the creative inspiration that was sown as a result of the Apollo Program. Visionaries like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson, who have managed to surmount the huge financial barrier to entry to start their own space companies, grew up in a post-Apollo world. It is only reasonable to believe that their fascination with the idea of space flight was inspired by watching human beings walk on the Moon we look upon. Companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic, as well as traditional industry participants like Boeing and hundreds of other companies that develop and build component parts, provide so many more opportunities now in the space industry than NASA alone could or did.

I have had the opportunity over the last several years to attend events sponsored by the UW Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and when I talk with today’s students in the Department, I see a great deal of enthusiasm and excitement towards the astrodynamics side of the curriculum. Its clear to me when I listen to the students that many more of them are interested in pursuing careers in the space industry than when I was a student at the UW. And, it’s understandable. There is an excitement and anticipation for new goals to reach and challenges to meet, and those have been too long missing in the space industry.

By the time of Sputnik in October 1957, I had already become an avid model airplane hobbyist expanding into my own homemade attempts at model rocketry, since the market had not been developed yet. I experimented with a variety of propellants, from black powder to asphalt-based GALCIT composite. It is a miracle that I didn’t blow myself up or burn down the apartment house in which we lived at the time. I am amazed that my parents let me do these activities without any constraints – bless their hearts!

Read more from Adam Bruckner . . .

The successful launch of Sputnik was a seminal moment for me. I remember exactly where I was and what I was doing when I heard of it from a neighbor – I was walking to the local drugstore to buy chemicals for my rocket experiments.

After graduating from McGill University in May 1966, I left for Princeton University to work in the Electric Propulsion Lab for the summer and then to start in the doctoral program in the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department. My research focused on a class of electric space thrusters known as MPD arcs. Thus, I was in Princeton during the seminal events that led to the Apollo 11 lunar landing.

The lead-up to this remarkable achievement was a nail-biter. In January 1967 we heard the tragic news of the Apollo 1 fire during a routine exercise at the Kennedy Space Center that claimed the lives of three astronauts. It was tragic, and people began to doubt whether we would ever go to the Moon.

However, NASA forged ahead with the Apollo 7 mission, the first of the Apollo manned missions. Even though it was confined to low Earth orbit, it was a huge relief that NASA was back on track with its lunar program. Apollo 8 quickly followed This mission was a huge gamble, in that it was the first time that a full-up Saturn V vehicle was launched with a human cargo.

The emotions I felt at the time were indescribable. To hear astronaut Frank Borman address the world on Christmas Eve 1968 with a reading from Genesis sent chills up and down my spine. We had done it! We had circled the Moon, and we had also beaten the Soviets to it!

Then came July and the Apollo 11 mission. My girlfriend and I watched the launch of the Saturn V and all the Apollo-11-related newscasts from whichever of the two TVs in the graduate dorm was showing Walter Cronkite’s broadcast. The newscasts were at once thrilling and nerve-wracking!

The lunar landing sequence had all of us in the packed TV room on the edges of our seats and holding our breaths. The LEM was starting to run out of fuel and there was a field of big boulders ahead. Good grief. . . what’s going to happen?!

When we heard Neil Armstrong calmly announce “Houston, Tranquility Base here, the Eagle has landed,” the room burst out in a deafening roar of a cheer! We were all beside ourselves. Wow! Wow! Wow! Supercalifragilisticexpalidocious!

The greatest human endeavor, ever, had been achieved, and so well! If we, humans could put one of us on the Moon, then we could do anything! All of a sudden, nothing seemed impossible! That feeling stays with me today, 50 years later.

For me, Apollo 11 reinvigorated my determination to take my research to a successful outcome, which I did. “If we can land a man on the Moon, I can do this,” is what I kept telling myself. I have used that mantra often over the years.

My only disappointment with Apollo was that it happened so fast! I missed out on contributing.

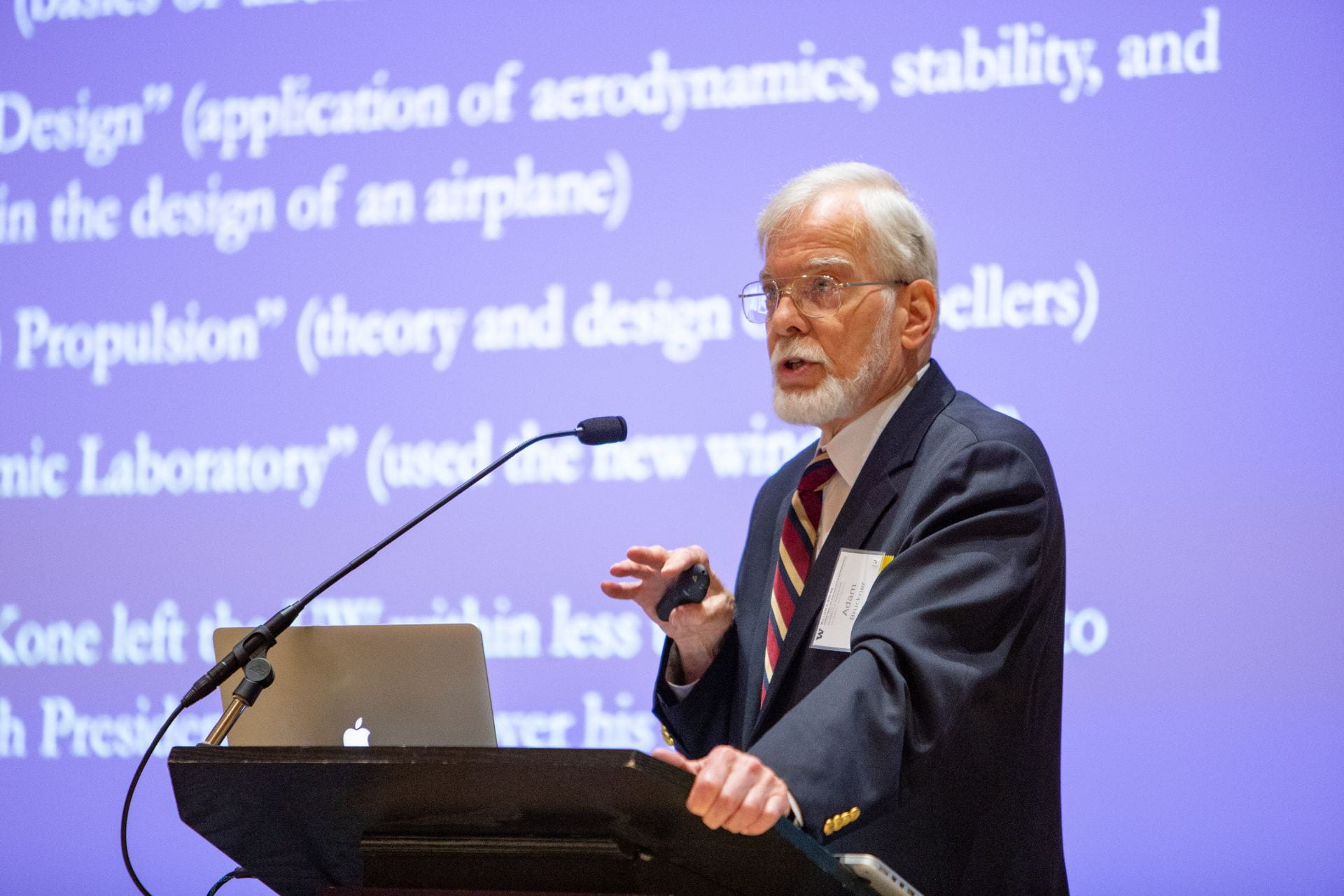

Adam Bruckner

Professor Emeritus, UW Aeronautics & Astronautics

“The greatest human endeavor, ever, had been achieved, and so well! If we, humans could put one of us on the Moon, then we could do anything!“

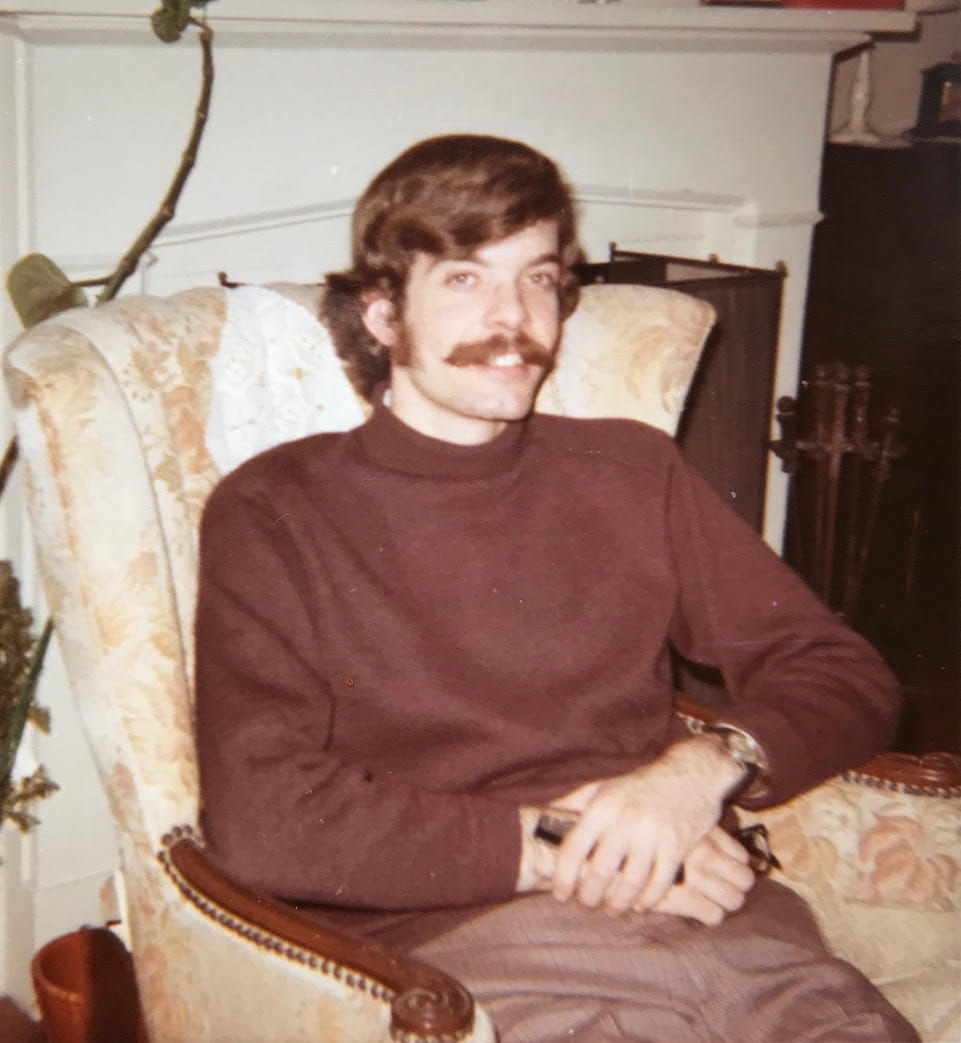

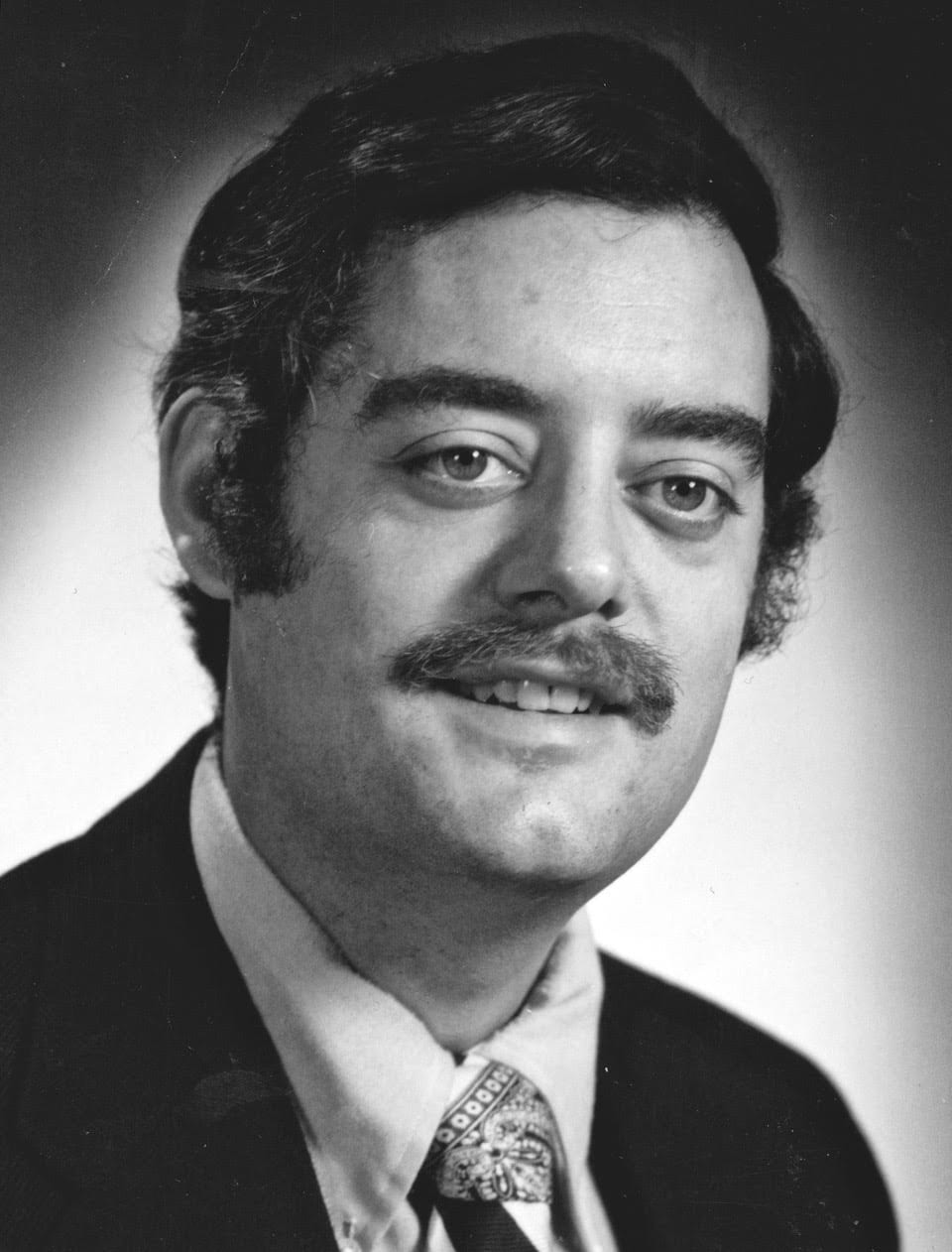

Above left: Adam Bruckner as a graduate student in the Apollo era. Above: Bruckner at the UW centennial celebration for aeronautics instruction.

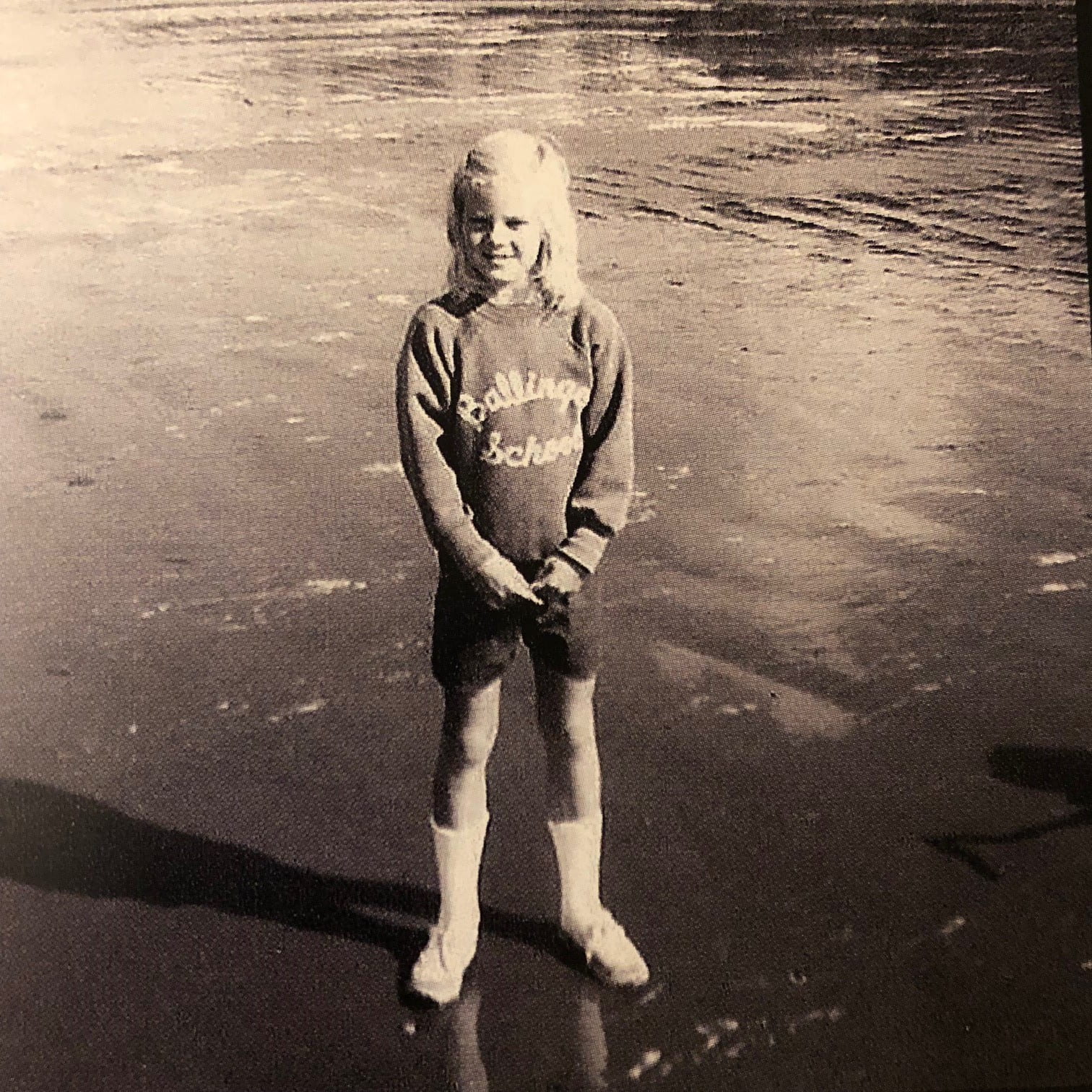

Laura McGill

Aeronautics & Astronautics Distinguished Alumna 2018

Vice President, Raytheon Missile Systems

UW BS A&A 1983

“The incredible accomplishments of the Apollo program were a significant influence in my decision to pursue a career in aerospace engineering. It started right there, and continued to be fostered by my parents, teachers and the many engineers and leaders that further progressed the science and technology.”

Above right: Laura McGill in her Ballinger Elementary sweatshirt in the Apollo era. Above: Laura McGill at the UW centennial celebration of aeronautics instruction.

On the afternoon of 20 July 1969, my entire family, grandmother, mom, dad, my older brother and two younger sisters were all gathered around our small black and white TV to watch the broadcast as the Apollo 11 Lunar Module first landed on the moon, and then as Neil Armstrong took the first steps on the surface a few hours later. I recall that the greatest trepidation was during the landing of the Lunar Module and whether or not the surface would be solid and flat enough.

We all cheered when we heard that ‘The Eagle has landed,’ amazed at the incredible achievement in which we were sharing. And in spite of the bright summer day outside in our Seattle neighborhood, we stayed fixed around that small TV with the grainy images to see all of the coverage.

Read more from Laura McGill . . .

Watching Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin step foot outside the Module was one of those eventful moments in history, for which you will always remember where you were and who you were with.

I had just turned 9 years old a couple of days before, but we had been following the Apollo missions from the beginning. As I grew older, I read about the earlier Mercury and Gemini missions and the biographies of the first seven Mercury astronauts – they were my heroes. I was also in awe of the technology that had allowed the men and women of NASA, along with the larger Aerospace Industry, to accomplish these missions. To my young mind, aeronautics and astronautics held the most promise for continued advancements to the capabilities of mankind, and I knew that I wanted to be part of it.

The incredible accomplishments of the Apollo Program were a significant influence in my decision to pursue a career in aerospace engineering. It started right there, and continued to be fostered by my parents, teachers and the many engineers and leaders that further progressed the science and technology. I feel a great debt to all of them and appreciate the opportunity during this 50th anniversary to celebrate the Apollo mission and the future that it opened up for me and many others.

Remembering Michael Anderson (1959-2003)

“It was just the adventure of it,” he said. “As a kid, I spent a lot of time watching science fiction TV shows—Lost in Space, Star Trek—and then I followed the real space program. It seemed like the ultimate thing to do.”

After watching the first moon landing, Anderson began memorizing the astronauts’ names. He was certain that one day his name would be added to the list.

– From The End of a Lifelong Journey by Nancy Joseph for Perspectives Newsletter, March 2003

US AF Lt. Col. Michael P. Anderson, UW B.S. Physics 1981, lost his life in the Columbia Shuttle disaster in 2003. He had talked about the Apollo mission to the Moon as an influence in his path toward becoming an astronaut. His first flight in space was on the Endeavor in 1998 to resupply the Russian Mir space station.

Michael Anderson in his official NASA portrait.

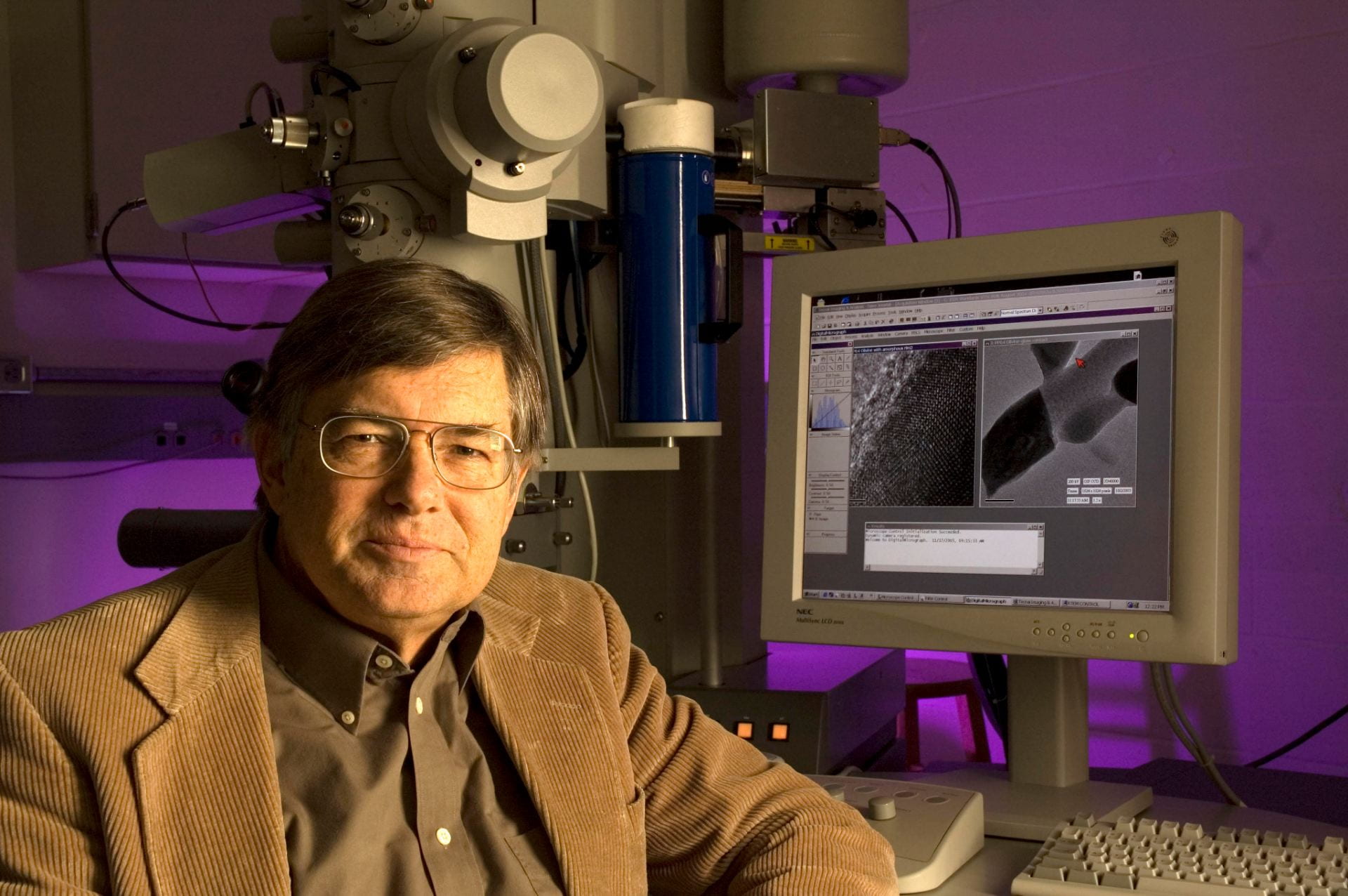

Donald Brownlee

Professor Emeritus, UW Astronomy

UW Ph.D. Astronomy 1971

“Besides actually working on pieces of the Moon, one of the great thrills of working at NASA was when a recently returned crew would give a travelogue of their mission at the next lunar science meeting. It was like listening to relatives show slides of their summer trip to Yellowstone but these were stories from the Moon.”

Above right: Buzz Aldrin in the hatch of Gemini 12 holding the S12 micrometeorite experiment containing collectors made of aluminum, gold, copper, plastic and glass made in the UW Physics machine and glass shops. Above: Brownlee in his UW lab.

When I was a beginning UW astronomy graduate student, I had the extraordinary fortune in 1966 to fly micrometeorite collectors on Gemini 10 and 12. We made the collectors in the Physics Shop, and the experiment was eerily similar to what was described in the novel Andromeda Strain that came out just a few years later. Michael Collins flew on Gemini 10, and Buzz Aldrin retrieved the second collector from the outside of Gemini 12.

I had always had an abnormal interest in rockets and space and this was a very exciting time. It was a great thrill to watch all the missions of the time but especially Apollo 8, the first to orbit the Moon, and 11, the first to land.

Aldrin and Collins along with Neil Armstrong were the crew of Apollo 11. Apollo 12 set down next to the Surveyor III spacecraft that had landed on the Moon in 1967. The astronauts cut parts off of it, and I was given some of them to work on because of my experience with micrometeorite craters on Gemini.

Read more from Donald Brownlee . . .

Just like that, I was a lunar scientist, and I spent an enormous amount of time working in Houston. I was usually in building 31, where the lunar samples were worked on, in what was then called the Manned Spacecraft Center. At lunch in the MSC cafeteria, I would often see Apollo crews. In the morning and evening you could see groups of three (the next crews) jogging across the vast open fields at the facility.

Besides actually working on pieces of the Moon, one of the great thrills of working at NASA was when a recently returned crew would give a travelogue of their mission at the next lunar science meeting. It was like listening to relatives show slides of their summer trip to Yellowstone but these were stories from the Moon. Real stories, real exploration by real people. It was all just beyond imagination.

I miss those unique personal travel stories but last March at the 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston, I was again electrified to hear Jack Schmitt, the only scientist to visit another world, talk about his exciting Apollo 17 mission and the wonders they found such as deposits of orange volcanic glass. His partner on Apollo 17 was Gene Cernan, the last person to walk on the Moon.

The human exploration ended in 1972 but the study of the rocks they returned vigorously continues and the information from them revolutionized our understanding of the Moon and the early evolution of large solid bodies in the solar system. They provided evidence that our moon formed by the impact of a Mars-sized body and that bodies like Earth and the Moon had violent early histories that included melting of their surfaces to form deep magma oceans.

In the summer of 1969, I was going into third grade. I lived in Chicago with my parents and seven siblings. Our family was all abuzz about the Apollo Program as was everyone else we knew. Years later, we found out our dad worked on Saturn V.

Read more from Susan Murphy . . .

He couldn’t tell us at the time because it was a secret project. He was a mechanical engineer and working as a contractor to Boeing. Apollo 11 was launched by a Saturn V expendable launch rocket. The “V” designation originates from the five powerful F-1 engines that powered the first stage of the rocket. I know we would have been bursting with pride the day Apollo 11 landed had we known our dad played a small part in it. My dad was so thrilled when I went to work for Boeing years later.

As it turns out, I don’t remember much more about Apollo 11 except that our family television was broken, and we all sat around my older brother’s 9-inch black and white television to watch. It was a proud moment for Americans.

Susan Murphy

Affiliate Professor, Aeronautics & Astronautics

Retired Senior Project Manager, Boeing

“Years later, we found out our dad worked on Saturn V. He couldn’t tell us at the time because it was a secret project. He was a mechanical engineer and working as a contractor to Boeing. Apollo 11 was launched by a Saturn V expendable launch rocket.”

Left: The Saturn V rocket on the launch pad, May 20, 1969. Susan Murphy later found out her dad had secretly worked on its development. Photo credit: NASA.

Roger Myers

Member, Aeronautics & Astronautics Visiting Committee

Retired Executive Director of Advanced Space Programs, Aerojet Rocketdyne

“News about space and the Apollo program was all around us and I was super excited about each and every mission, devouring all the magazine articles and books I could get ahold of.“

Above right: The poster NASA sent to Roger Myers in Paraguay when he was a child. Above: Myers holding an electrical ion-drive rocket motor that could be used for a future Mars mission.

I was a young kid when Apollo 11 landed on the Moon, living in Bogota, Colombia. My father was a naval engineer working for the Inter-American Development Bank. My parents always encouraged their kids to learn about science and to pay attention to big events in the world, and in the 1960s the most exciting field in science was space exploration and the quest to put humans on the Moon.

Living in Colombia, I didn’t have access to hobby shops or many traditional American toys, so my Dad taught me to make my own – and I did: airplanes and rockets made from wood and shaped pieces of scrap metal that I would play with endlessly.

Read more from Roger Myers . . .

News about space and the Apollo Program was all around us, and I was super excited about each and every mission, devouring all the magazine articles and books I could get ahold of.

I vividly remember the night Apollo 11 landed on the Moon and when Armstrong and Aldrin descended to the surface. It was late at night (for a child) in Bogota, but it was such an historic event that my parents let my sister and I stay up to watch.

So – what did Apollo mean to me? It set the direction for my life. I watched all the missions (as best I could from Colombia), and was totally hooked. After Colombia, my parents moved to Asuncion, Paraguay, and I spent a lot of my free time building rockets. When I was a teenager my parents helped me create a laboratory at home and I built and tested all kinds of small rocket engines – I was always experimenting with different propellant combinations and trying to figure out how to measure rocket engine performance more accurately. I couldn’t buy model rockets in Paraguay!

I was just as excited when I had a “rapid unintentional disassembly” as when I had a successful test. I never really wavered – rockets were, and are, in my blood. My specific focus on advanced spacecraft propulsion, as opposed to launcher propulsion, all derives from the Saturn V poster that NASA sent to me in Paraguay – I saw that the only part of that huge vehicle that came back was that tiny capsule and decided that I wanted to help improve the payload fraction that could be delivered by rockets to their destination.

That focus led me to work on improving the performance of spacecraft propulsion systems. From graduate school at Princeton to NASA’s Glenn Research Center to Aerojet Rocketdyne in Redmond, I have had the good fortune to help drive a revolution in spacecraft performance through the development of high-performance electric propulsion systems, which are now used on over 300 spacecraft and will be a key element of the Lunar Gateway.

All because Apollo set me on this path.

I have been a space cadet most of my life. I was delivering the morning paper when Sputnik launched and I can still remember the Headline “USSR launches Artificial Moon.” I sat down and read the entire article before I went to the next house to deliver their paper. I cut clippings out of the local paper for each space launch and saved them in a scrapbook during middle school and high school. I took all the space-related courses in the A&A department and my Ph.D. was in rocket propulsion.

Read more from Dana Andrews . . .

I, like most of my astronautics friends, know exactly where we were when Apollo 11 launched, and when the Eagle landed. Neil and Buzz were only in the cabin for a few hours and then they took their moon walk. One thing that was amazing is that the world essentially shut down for those few hours. Wars and crime essentially took a vacation so everyone who could get to a TV could watch the landing and then the moonwalkers. It was probably the first worldwide event watched live by a significant portion of the planet.

It was a huge political success for the USA, not that it made any difference in the Cold War, but we all could hold our heads up a little higher. The bigger success was the huge improvement in STEM education and the spin-offs from all the technology advancements made to enable Apollo 11. We got solid-state digital computers, new alloys for engines, fuel cells, cryogenic insulation, high frequency communications, and dozens of other breakthroughs that drove our economy higher and made us the envy of the world. Many of today’s “Tech Billionaires” got their start as a result of the improvements in STEM education and the technologies spun-off from the Apollo program.

Now, fifty years later, it almost seems surreal. That a group of men and women could start with captured V2 rockets, build an entire technical infrastructure, and go to the moon and back in less than ten years seems impossible. It was a special time and a special group of people. Many of them are gone now, but we should take the time to celebrate their accomplishments appropriately. As it turns out I will be a cruise ship in Northern Norway on July 19 of this year, but I plan to tip a few in their honor.

Dana Andrews

Member, Aeronautics & Astronautics Visiting Committee

Retired CTO, Spaceflight Industries

UW BS A&A 1966

“One thing that was amazing is that the world essentially shut down for those few hours. Wars and crime essentially took a vacation so everyone who could get to a TV, could watch the landing and then the moonwalkers.”

Left: Dana Andrews in the Apollo era studying at Stanford University. Above: Dana Andrews at the UW centennial celebration for aeronautics instruction.

Rao Varanasi

A&A Distinguished Alumnus 2019

Member, Aeronautics & Astronautics Visiting Committee

Affiliate Professor, Aeronautics & Astronautics

Retired Chief Engineer, Boeing

UW Ph.D. A&A 1968

“I was excited by the tremendous opportunities in the field and decided to pursue a doctorate degree at the UW in aeronautics. The Department changed its name from Aeronautical Engineering to Aeronautics and Astronautics about a year after I entered the program.”

Above right: Usha and Rao Varanasi.

When I was a foreign student from India enrolled in a graduate program in mechanical engineering at Caltech in the early 1960’s, I was exposed to the exciting activities in aerospace in the U.S. from the various presentations to the graduate seminar class by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena during that post-sputnik era.

Read more from Rao Varanasi . . .

I was excited by the tremendous opportunities in the field and decided to pursue a doctorate degree at the UW in aeronautics. The Department changed its name from Aeronautical Engineering to Aeronautics and Astronautics about a year after I entered the program.

My personal reflections on the lunar landing were that I was extremely proud of the event. I remember watching the event breathtakingly with my wife Usha on our television set in our apartment. When Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon successfully and uttered his famous words, we had a sigh of relief followed by excitement. Two thoughts came to my mind I recall; that Neil Armstrong was an aeronautical engineer and that this monumental and proud American event happened during Richard Nixon’s presidency by happenstance, as Nixon was not my favorite president.

It was undoubtedly the greatest moment in our space exploration. I was moved to get many memorabilia of the event including 10 large official photographs of the lunar landing and 13 large copies of paintings commissioned for this occasion from NASA, which I still have.

It was a good year, 1969. Apollo 11 was between high school graduation, and starting freshman year at the UW. It looked like a great time to be aiming for a career in what we then called “the space program.” Only 20 years later, it was clear that the biggest surprise about Apollo missions to the Moon was that we quit going.

Now it’s 50 years later, and not only have people not gone back to the Moon, the U.S. hasn’t been capable of launching its own astronauts to orbit since the Space Shuttle was retired in 2011.

There is so much to go back for on the Moon. The surface area is equivalent to the combined areas of Africa and Australia. Saying “been there, done that” is as if aliens visited one flat “safe” spot each in the Sahara, Mojave, Gobi, Atacama, Negev, and Antarctica deserts–and concluded there is nothing interesting about Earth.

Read more from Anita Gale . . .

The highlands on the lunar far side have been pummeled for billions of years by everything the universe can sling at it, and we cannot predict what may have been created by impact chemistry in vacuum, extreme temperatures, and low gravity.

Even without boots on lunar ground, there is an excitement about the poles: craters of eternal darkness, peaks of eternal light (energy!), chemical signatures of water (air and fuel!) and ammonia (nitrogen!), and hints of more interesting stuff.

Finally now, there is renewed interest in the Moon. In the self-declared space settlement technical community, we see the Moon as a place to do business, the primary source of materials to build and grow the human economy into cis-lunar space.

We are roadmapping infrastructure development, analyzing processes and economics to supply commodities from lunar and asteroid materials, talking with Congress about property rights and legal frameworks to enable industrial development, and cheering on billionaires and NASA as they make progress to get us back to the Moon. And stay there this time.

Anita Gale

Retired Senior Project Engineer, Boeing

Co-Founder, Space Settlement Design Competitions

UW BS A&A 1973 and MS A&A 1974

“Apollo 11 was between high school graduation, and starting freshman year at the UW. It looked like a great time to be aiming for a career in what we then called ‘the space program.’ ”

Above left: Anita Gale in 1986 during her work for the Space Shuttle program. Above: Gale at the UW centennial celebration of aeronautics instruction.

Nominate a UW colleague

Nominate yourself or a member of the UW family who has been influenced by the Apollo missions to be included in this project.